Literary Cocktail Hour

The Literary Cocktail Hour is a fun, informal monthly event featuring a pair (or more) of speakers in an entertaining, illuminating virtual event based on the notion of a cocktail hour.

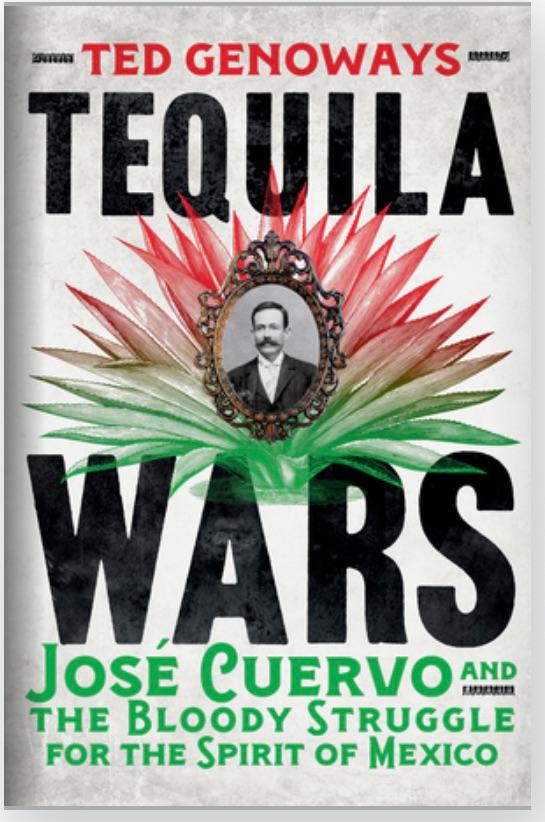

Tequila Wars:

Tequila Wars:

José Cuervo and the Bloody Struggle

for the Spirit of Mexico

By Ted Genoways

Friday, May 9, at 5:00 pm

Online and free!

Ted Genoways is a two-time James Beard Award winner and the author of five previous books, including This Blessed Earth.

His reporting on the tequila industry has appeared in Bloomberg Businessweek, The Daily Beast, Mother Jones, and received the Association of Food Journalists’ Award for Best Writing on Beer, Wine or Spirits.

He is a President’s Professor at the University of Tulsa, where he edits the literary magazine, Switchyard.

Tequila Wars:

Tequila Wars: